By Megan Palmer-Abbs (Innovation School, Glasgow School of Art), Keith Halfacree (Swansea University), Jesse Heley (Aberystwyth University) and Café participants.

Thanks is given to the four presenters in the earlier related conference session who opened the floor for further discussions http://conference.rgs.org/AC2019/053c8c22-690d-4630-b509-5f5b369a673f .

‘[R]eport of my death was an exaggeration’ (Mark Twain, 1897)

Rural or peripheral areas are frequently depicted as places of lesser qualities, often disadvantaged by their remoteness and wholly inadequate access to services and new technologies, depicted as lagging behind more developed largely urban areas. If not so disparaged, they may instead be romanticised as places set in time, rural idylls preserved in aspic for those who wish to ‘visit’ and enjoy notions of prettiness. Both representations, in sum, largely depict the rural as more dead than alive in terms of its everyday rhythms of life. And yet, in contrast, rural areas can instead be recognised as places of resilience and resourcefulness, impacted by, responding to and even initiating the troubles and tribulations that are expressed through both indigenous and endogenous events. Thus, current global memes, such as climate change, digitisation, migration, Brexit, to name a few, engage rural communities in many ways. One may even suggest that it is how rural communities (and individuals within them) meet, face and engage with these challenges that ultimately make, re-make and often transform the identities of rural spaces.

This brief report stems from a group of researchers, professionals and young adults who came together under the Rural Geography Research Group (RGRG) at the Rural Resilience and Resourcefulness Innovation Café, held at the Royal Geographical Society with Institute of British Geographers Annual Conference 2019. This less formal conference session gathered to discuss and deliberate the challenges and opportunities current facing rural spaces. Drawing from our wide and varied experiences and expertise in rural development, we examined the changing but defiantly still alive and expressive voice of rural geography in a rapidly changing world.

Discussion in the Café was framed by the following questions:

- What are the current imbalances and inequalities experienced in rural spaces?

- How, and does, this drive entrepreneurship and innovation in these places?

- What concepts and framings can we derive from these that best represent rural spaces?

This report endeavours to articulate agreed – sometimes disagreed – outputs from this short session that we hope can act as a catalyst for further discussion and future research ideas. Certainly, it reinforces a core message that rural voices are, like Mark Twain in 1897, far from deceased.

Method

Inevitably in a conference, the session was predominantly attended by Human Geography academics with an interest in rural geography. Nonetheless, participants were inter-generational and with a range of academic experience from undergraduates to senior researchers. Participants were split into two working groups of approximately ten people, each reflective of the diversity of attendees (age, gender, experience). Both comprised predominantly UK citizens but with a few international participants (New Zealand, Germany, USA). Each group was given a flip chart, sharpie pens and space to work and were asked to debate and document each research question for approximately 20-25 minutes. A group representative then gave an overview of each group’s findings, and differences and similarities discussed. Some of the overall findings and impressions from the Café are now presented, under the three headings of the questions noted above.

1. Imbalances and Inequalities

The context within which we observe and debate imbalances and inequalities in rural spaces remains wide and varied and yet is often specific to the space under observation. Nonetheless, participants strongly agreed that many of the topics were not new and that, moreover, current issues added further dimensions and urgencies to long-standing concerns for rural geographers.

The theme most discussed at the workshop was that, despite policy ambition and increased articulation of rural place-based needs, inequality between urban, rural and intra-rural spaces still feels very real and prominent. Whether this be at the level of individual human experience, policy or physical expression, it was commonly accepted that existing urban versus rural dichotomies remain, albeit often expressed as peripherality, urban-centric policy or inaccessibility.

More specifically, it was generally agreed that current social, political and economic transformations in rural spaces could be linked to things such as the tensions which have resulted in the remain and leave geographical tapestries of the Brexit debate. Austerity measures’ consequences, shifts in global markets and cuts in public spending on critical rural services had all become entangled with political views over time and across space and could often be evidenced via specific impacts at the local level.

Elsewhere, the ongoing importance of rural research around accessibility was emphasised, including access to transport, education and healthcare. In respect to the latter, the impact of drugs on rural communities (and notably in regard to the opioid epidemic in rural USA) was deemed to be of growing importance. Here, the comparatively limited body of existing work on this theme was noted, which may in part reflect a wider but mistaken view that ‘drugs’ are an ‘urban problem’. Demographic trends were also discussed, including the ageing countryside and the disproportionate impact this may have on rural communities and economies. This issue was also connected to healthcare provision. However, it was felt that a potentially myopic view of ageing in rural place could and should be avoided, making explicit contrast with other research which demonstrates the value of and contributions made by older people in rural contexts. This includes their role as custodians of knowledge and practises, as well as the significant role they can play as providers of key services as formal and informal volunteers and carers. The elderly in rural areas can certainly help to develop overall place resilience.

The Global North, the UK in particular, framed much of this discussion. The current trend here in policy to move or replace public sector responsibilities with local initiatives was seen as critical turn of events. This shift in responsibility, perceived as focused on old and outdated organisations, social structures and communication methods, was seen as magnifying rather than reducing existing feelings of marginalisation in rural communities. This could easily reinforce individual senses of disenfranchisement and disconnection from contemporary power elites. (It was recognised that rural communities in the Global South are likely to identify in a different way with this narrative and it was felt that greater research from this area is required.)

The narrative used to portray rural spaces was also discussed in the context of the debate on how land and land use are valued more broadly, financially and otherwise. Participants felt that despite successful rural businesses, particularly in the renewable energy, agriculture and tourism sectors, paying into central societal funds (principal taxes), rural spaces are still regarded and narrated as a cost burden to the country and its people overall, yet also as having little resource and service equity with urban areas. Coupled with this was the noting of wider public scrutiny of rural land use and its implications for climate change and land degradation. Café participants noted, however, that those living outwith rural spaces held a certain collective responsibility as consumers of rural activities, yet often failed to appreciate this fully. This was seen as exacerbated by public misconceptions of rural spaces presented via multiple communication methods but increasingly through social media.

It was also acknowledged that some rural communities held higher levels of human capital and were better able build a sense of community and individual resilience than others. It was felt that more resilient communities tended to be endowed with greater numbers of change agents and risk takers, with adversity enabling the building of character and a ‘do-it-yourself’ approach. Communities which lacked access to such assets were less likely to build capacities to change their circumstances and harness capital in this endeavour.

2. Entrepreneurship and Innovation

Opinion onentrepreneurship and innovation in both groups swayed towards people’s ability to act as a ‘change agent’ or activist and the variability and success of such individuals in motivating, shaping and supporting resilience in communities. Such ability and its will to create a resilient community were seen, however, as very varied. Groups also felt, though, that the collective ability of a community to access assets and resources was of equal importance to individual ability. Access to resources and assets – often intrinsically entwined in current organisations and community and individual relationships but often functioning in isolated spheres with differing agendas – was seen as a major barrier to change at all levels of decision making. Again, it was acknowledged that the discussions the groups were having here appeared similar to previous research findings but that the current context was viewed as being very different. This different context for the rural today was seen to be of great importance in shaping the future of rural geography.

The groups agreed that at the centre of discussions should be the importance and place of community development and the ability to respect and harness inter-generational knowledge and skills. They generally agreed that older residents offer significant potential to underpin rural community resilience. Understanding intergenerational politics, with gender also cross-cutting this, was highlighted as being a critical ongoing focus for research (particularly outside the Global North). Examples raised in the discussion included the role of mobile phone technology in rural India, which has potentially bypassed (aspects of) the need for hard-wired telecommunications, and the role that virtual platforms might play in facilitating the local economy.

3. Concepts and Framing

A wide range of topics were discussed under this umbrella heading, which the Groups categorized under broad, inter-related sub-headings.

Reflection of Research

Participants firmly concluded that, in order for research to be of greater relevance and impact, rural geographers should revisit the issue of language and address a proliferation of jargon. This was seen further to reflect a tendency for academic rural geographers to converse in an institutionalized manner, which cuts down their capacity to engage usefully both with other fields (development studies, etc), as well as in policy, media and public settings.

Mindful of this language issue, groups felt that demonstrating value is very much allied to aspects of justice and ethics outside of just large meta-narratives. There is a tendency to talk to concepts such as neoliberalism and global trade, with much attention focusing on how these are characterized, defined and are transforming. However, outside of academic circles, these terms may be of little obvious everyday immediate importance to policy makers, practitioners and people living through these conceptual frameworks. Therefore, rural geographers need to reflect more fully on the focus and direction of conceptual debates, as well as the nature of suitable evidence.

Research and Policy

The groups decided that as rural geographers we need to explore and develop empirical evidence which supports evidence-based policy. Yet, as academics, we should also be wary of the role of policy driven evidence-based recommendations and activities alone. More specifically, the groups agreed that there should be an emphasis on demonstrating the value of rural research across a range of scales, particularly in more local settings, and on emphasizing the value this can bring to decision makers. In this respect, they recognised that the mantra of ‘thinking globally, acting locally’ was often ill-used and misrepresented. There is a need for us, as academics, to articulate better how global processes and networks are embedded in localities (food networks, carbon storage etc). Within this sphere, it was also recognised that rural space is as implicated in globalization as urban space, rather than somehow existing ‘in its own right’. Contexts fashion globalization in relational ways and a rural context was no different in this respect.

Re-evaluating Approaches for Rural Change

The groups agreed that as academics we need to make research more visible and valuable and that this role rests in many ways on inclusivity and participation. The need for more genuine efforts to engage with communities in research design, as well as in data collection and dissemination were all noted. It was also agreed that the balance of power in setting research agendas needed revaluating and a much more hands-on approach taken. The groups felt that, in the future, the level of community involvement in the production of research agendas may heavily influence how research funds are not only targeted but also sourced.

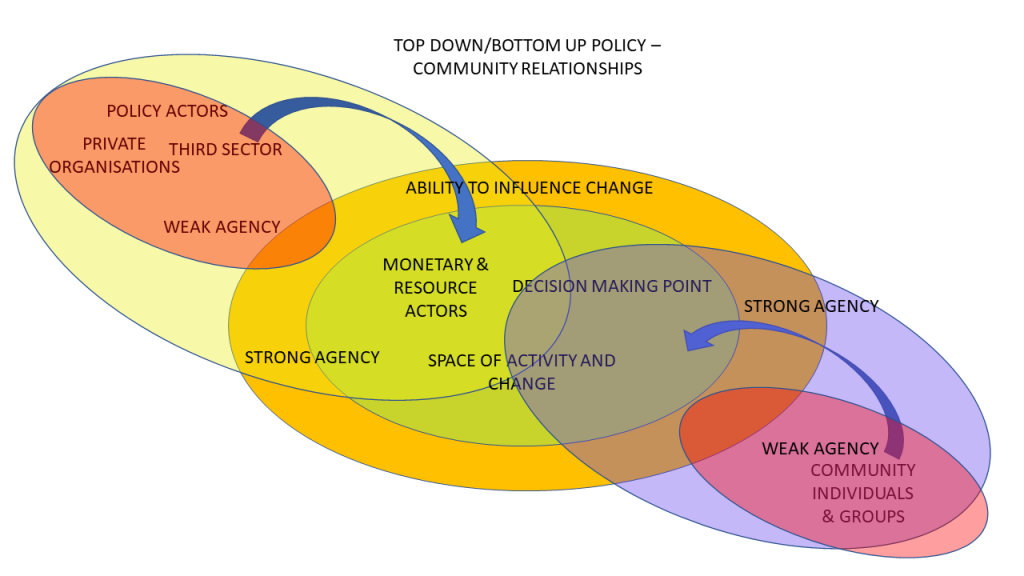

In order for academics to appreciate rural places today more appropriately, participants agreed that a strong sense that there was an imbalance in the very sense of community itself, and of collective and individual identity(ies) of those who lived and worked in those communities, must be recognised. This is representative of power relations between all the actors who contribute to these rural spaces. The groups felt very strongly that mixtures of weak and strong agency, regardless of the configuration and interrelationships of actors, stifles positive change in rural communities. Whilst this is not a new phenomenon, political elites still hold noted positions of authority through existing governance and organisation structures and activities, such as in fund allocation and resource and service provision.

Resources for community development are not easily accessed. Even when secured, development can be too policy-led and not reflective of community needs, hindering the ability to find placed-based solutions to local issues. In addition, diminishing services due to public spending cuts and a new approach to transferring responsibility for local development back to communities is rife with challenges.

Groups further agreed that when all actors or agents in community development are in a position of relative equality to make collective decisions (strong collective agency) then the most positive steps are made in community development. Change becomes less dominated by a priori policy and allows a space for co-production, central goal decision-making and creating new structures and methods. This removes the siloed approach of responding to community needs and builds on shared strengths and aspirations (collective goals). Figure 1 illustrates where spaces of positive change can occur when collective groups co-produce informed local-based decisions.

Figure 1: Spaces for Change and Strong Agency

The groups further agreed that relationships within spaces associated with such emotive expressions as belonging, protecting or memorialisation could play a key role in shaping just how these spaces (remain un)changed. An idea of maturity of change and of the language associated with transition(s) was discussed. Groups agreed that there is a need for common language and perspectives between urban and rural and also intra-rurally.

Framing the space of change

Framing the space of changewas seen by participants as a significant challenge if we are to enable rural spaces and their inhabitants to adapt, brace and build in change capacities that will create more sustainable futures. The concept of ‘language of spectrums’ was discussed in terms of capturing the whole array of views present in rural spaces. This approach was seen as a way forward in acknowledging that rural spaces are shared. Groups felt it important to recognise differences as positive, acknowledging and working with sometimes opposing views in debating and deciding upon how to achieve ultimately shared goals.

The groups decided that greater understanding of value was needed as it was evident that perceptions of rural spaces and their attributes, assets and resource use were fraught with multiple evaluations. With rural spaces temporally changing, multi-dimensional and diverse, who decides what is important, relevant and beneficial in these spaces requires a joined-up, cohesive approach where trust, seeking shared goals and expressing more even power relations are paramount. This can only be achieved if policy-led development achieves a different kind of relationship with local needs, whereby actions framed and responsibilities taken in achieving long-term sustainable development are shared and prioritised. Groups agreed this must be local in nature (relational), whilst responding realistically to wider drivers, such as global economies, climate change and social restructuring. Consequently, new working relationships between money-holders and development-makers that are de-politicised, more equal in power relations and working towards common shared goals are required. These new relationships should use knowledge and fiscal endowments as shared assets rather than as ‘power tools’.

Framing concepts of change

The Café groups agreed that the empowered community as a vehicle for change that accommodated both declining state intervention and active community-based development was essential. However, this is easier talked of than achieved, with current top-down and bottom-up approaches both deeply embedded in existing social systems and organisation structures. Groups agreed that moving towards co-production of space, with all parties (state, third sector, communities, individuals) positively part of change, is fraught with challenges for all. However, the following are ideas the groups produced to help seek a way forward:

- Shared imaginings. This meansco-production of future aspirations and goals for a shared vision. It can only occur if the format and groups who determine outcomes are collective and participatory. There are many skill-sets within research that could help enable this in a non-biased independent manner, brokering between the many agents involved in any desired sustainable rural development. Research into such activity is apparent but much better ‘buy-in’ is required from all involved to achieve firm foundations for new ways of working. This should be seen as long-term action rather than short-term ‘pop-up’ meetings of parties. Further research and relationship-building between researchers, communities and policy delivery agents is needed. Yet, given the high profile of co-production and innovation for funders (e.g. ESRC, EPSRC) and a need for research impact, it should certainly be a significant focus for researchers.

- Recognised divisions. Rather than trying to mask over differences in communities, we must recognise and accept that difference can be good, positive and character-building for these communities. Such recognition can feed into identity and strengthen individuality within the collective. Acknowledging that no two communities are the same – why should they be? – does just mean that approaching challenges and opportunities (local-to-global) may have to be different and often quite specific.

- Multi-level trust. In order to move forward positively and embrace change, a sense ofsecurity and trust is required across all agents of change. Ability to appreciate differing perspectives whilst still achieving day-to-day goals is required. Such trust needs to be between any level and scale of agents: policy-community, community groups, third sector, individuals. In a dynamic and multi-complex space, a ‘levelling’ of power relationships and balance needs to be found.

- Flow and temporalities. The flow and temporality of rural changes do not necessarily match clear-cut or more fixed time-spans, such as those of policy funding. However, we must be responsive to near and far threats and to challenges experienced by those living and working in rural spaces. Examples to be responded to include climate change related natural disasters, planning for such events, economic shocks (local to global), demographic changes, and changing community characteristics (ageing, isolation, economic activity, in-migration of working-aged residents, delivery of services, and so on). This dynamic context is highly significant in shaping rural places today and engaging with it should be a priority for all those with the ability to facilitate and manipulate change.

- Future

re-thinking. Achieving long-term

sustainable resilient rural community spaces will be very challenging. All agents (policy, academia, third sector,

communities, individuals) must combine their resources in more collective ways rather

than act as separate organisations to drive the kind of changes required to

meet both current challenges and for future-proofing rural communities. In this respect, rural geographers and others

need to ask:

- What constitutes evidence for rural spaces that can support, resist or guide change?

- How do we rethink resources across spaces that are more than just urban versus rural but without losing the power of rural distinctiveness?

- How can rural communities become more resource-based and resourceful, and what is the role of researchers in these processes?

- How do we identify the principal spaces where positive change can happen rather than speak about but not realising aspirations?