Natasha Coleman

Twitter: ncc_96

Swansea University PhD Candidate, supervised by Dr Keith Halfacree, funded by ESRC Wales DTP.

Across the rural UK, the so-called ‘sporting estate’ remains a historical continuum yet their present status is increasingly diverse and continuing to evolve in response to changing pressures and opportunities. My PhD explores such estates positioning in the 21st Century, focusing particularly on the lived experiences of the various actors within these landscapes. Following an introduction to my research, this post reflects upon carrying out sporting estate fieldwork during a pandemic, how this context shaped what was possible, and how both physical and virtual connections to the landscapes researched have been meaningful.

Little appreciated by the general public, shooting estates cover ⅔ of the UK’s land area and contribute £2 billion to the economy (PACEC 2014). They employ around 3,000 people directly and 22,000 indirectly (National Gamekeepers 2021; PACEC 2014). Yet, the land they cover is under increasing pressure to produce multiple public benefits and adapt alongside major environmental and agricultural land management reforms (Mcmorran et al. 2020). Somewhat surprisingly, Social Scientific engagement with these estates and their connection to the controversial topic of game shooting remains slim (Hillyard & Burridge 2012), with very little consultation with and understanding of the lived perspectives of those within their boundaries (Brooker et al. 2018; McMorran et al. 2015). Further, growing up within an upland sporting estate community, I heard calls time and again for critics to witness their reality. For all these reasons, my research has sought to be phenomenological, focused on encounter and using figurative cases and stories from different estates. In Covid times, however, such a focus has been especially challenging…

~~~~

The reality of doing fieldwork during a global pandemic has been different from the ‘gentle geographies’ and ethnographic research I’d hoped for (Pottinger 2020), notwithstanding the controversial side of the topic. A desire to take time to build relationships and witness everyday pressures and opportunities was often cut short by revised plans and anything I wanted to do slowly or gently had to be re-considered.

During lockdowns and travel bans I researched shooting estates virtually, cataloguing information from web and social media pages, and conducted Zoom interviews with managers, owners and other stakeholders. I also kept an informal diary with a gamekeeper, allowing me to experience some of his year (Figures 1 and 2), there was notable limitation to how much interaction could be made with those on the ground. Gamekeepers are notoriously ‘hard-to-reach’ key informants (McMorran et al., 2020) so even with contact made I had to wait…

Finally, 8 months into my PhD’s second-year, travel was authorised. I left my homework space and travelled first to pheasant country…

~~~~~~~

It’s June. I’m standing in a field with *Simon*, a tall gamekeeper put into contact with through the Gamekeepers’ Welfare Trust. He points to an isolated oak’s bulbous roots (Figures 3 and 4) and tells me how the landowner tests his knowledge of the land by sending him zoomed-in photos of tiny aspects of the estate. From such a close-up he could now give that tree’s exact location; he knows every inch of the estate:

“Every single day… I have been on here, whether I have walked from this angle or over there or been… lazy… and driven around it… from that little bracken gully on the far size [points into distance], that is our boundary… From there you could blindfold me and take me and drop me, I know where I am. [Points] All that is [estate name], the forestry, the moor, it’s all and 30 years of Spaniels have died on this estate walking it… [O]ther than a gamekeeper who has been on a lump of ground for 10 years nobody will have a better knowledge. The shepherds… know their patch but… keepers are the only ones who know all of it”.

Such conversations lead to other territory: new policies and what they mean for that specific place, how estates are adapting, shifting focus, taking farms back in hand and diversifying or intensifying activities. Though shoots are still integral to the landscape, much change is happening. Simon knows pressure all too well…

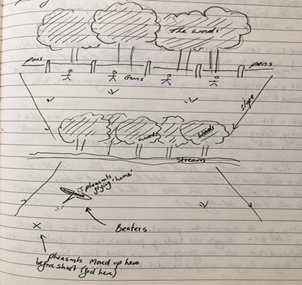

Another estate. A young keeper takes me to a field edge overlooking a valley. He draws lines across the horizon and points out how the land has been sculpted for gamebirds. He shows me how a pheasant’s life on the estate is a journey between the bottom and top of such valleys. He’s showing me what the shooting season build-up involves and where the birds fit into it all (Figure 5). I learn how landscape is physically shaped by the shoot, what the keeper’s role entails, and how his livelihood relies on a chain above and beyond estate boundaries.

I learn terms like ‘dogging in’ (Figure 6: the zigzag way dogs round up game birds and keep them in a certain area for feeding etc). I encounter working relationships between human and more-than-human, the language of this assemblage.

Overall, physical, and virtual presence in field sites have aided my understanding of these complex places, with webs of actors and actions both enmeshed and diverging. I have witnessed subtle nuances within place, seen new practices shaping landscapes: cider making, holiday lets, stopped hedgerow mowing, solar fields, intensifying farms, bigger game numbers, more public pushback. Covid, too, has highlighted shifts: challenges of increasing tourism, funding losses and fluctuations, changing human and inter-animal relations, resistance to forces for change. Old ways are tied into new and mark 21st Century landscapes of transition. Thus, Covid may have disrupted original gentle geography fieldwork ambitions, but I feel successful changed plans has added depth to my analysis. I’m now grateful to draw on a combination of virtual and in-situ fieldwork and hope that in highlighting how I’ve combined the two, others will note that the added work of re-configuring plans can be beneficial!

References

Brooker, R., Hester, A., Newey, S. & Pakeman, R. (2018) Socio-economic and biodiversity impacts of driven grouse moors in Scotland, at: https://sefari.scot/document/socio-economic-and-biodiversity-impacts-of-driven-grouse-moors-in-scotland-part-2

Hillyard, S. & Burridge, J. (2012) ‘Shotguns and firearms in the UK: a call for a distinctively sociological contribution to the debate’, Sociology 46(3): 395-410

McMorran, R., Bryce, R. & Glass, J. (2015) ‘Grouse shooting, moorland management and local communities’, Commissioned Report

McMorran, R., Thomson, S. & Glass, J. (2020) ‘The employment rights of gamekeepers’, Commissioned Report to the Scottish Government, at: https://sefari.scot/research/phase-2-grouse-research-socioeconomic-and-biodiversity-impacts-of-driven-grouse-moors-and

National Gamekeepers (2021) ‘About gamekeeping’, at: https://www.nationalgamekeepers.org.uk/about-gamekeeping#:~:text=There%20are%20about%203000%20full,is%20a%20very%20old%20profession

PACEC (2014) ‘The value of shooting’, at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2007.12.003

Pottinger, L. (2020) ‘Treading carefully through tomatoes: embodying a gentle methodological approach’, Area online, pre-publication: 1-7